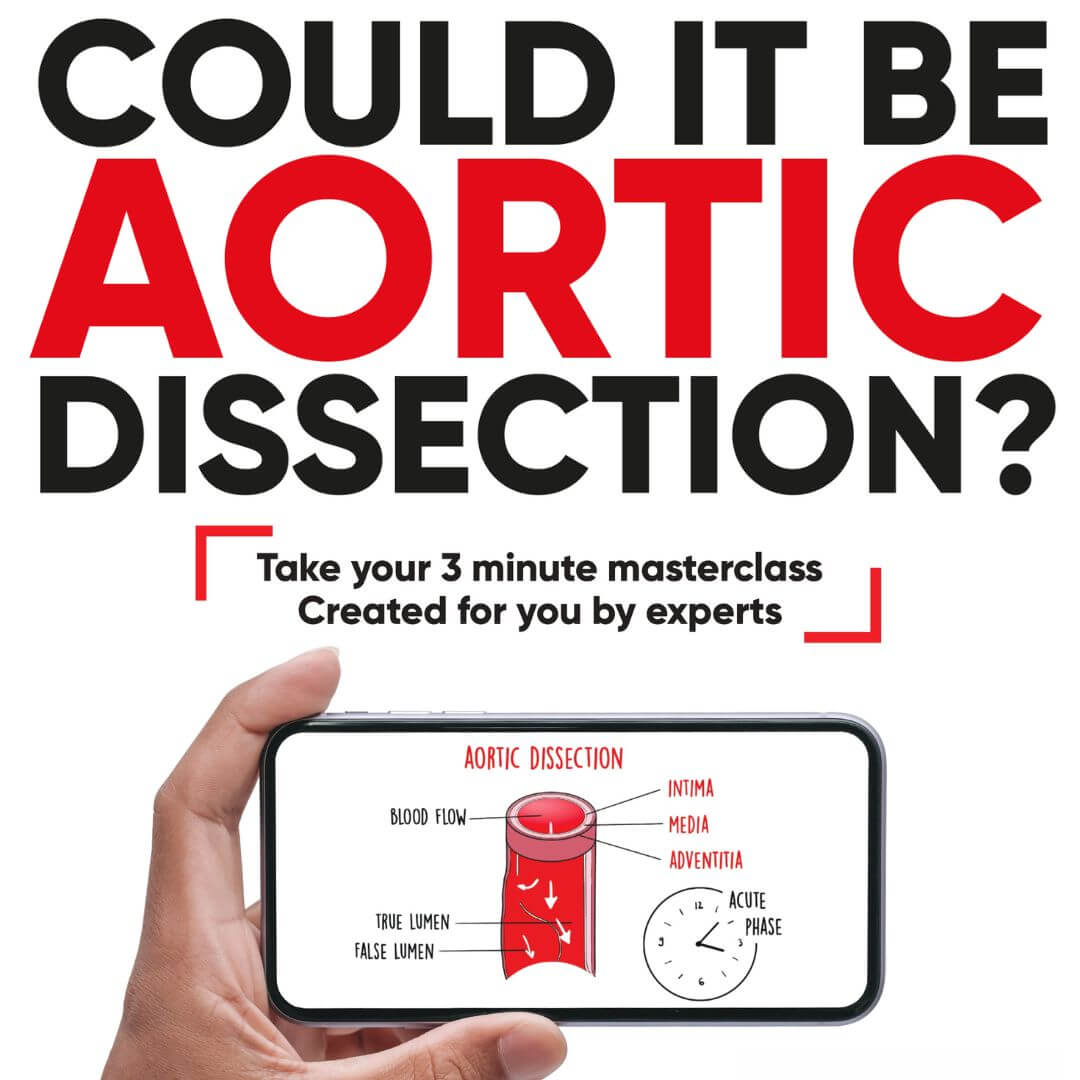

In the intricate world of medical emergencies, the diagnosis of acute aortic syndrome presents a formidable challenge, often likened to finding a needle in a haystack. This analogy, vividly depicted in the latest episode of The Resus Room podcast, highlights the gravity of this potentially fatal condition. The episode delves into the nuances of diagnosis, highlighting its frequent misdiagnosis and the consequential delays in treatment. The discussion focuses on groundbreaking research which sheds light on this elusive condition, exploring the intricacies of patient presentation and the effectiveness of current diagnostic tools in emergency departments.

Confronting the Challenge

Simon Laing, EM Consultant, Bristol Royal Infirmary

“So looking at acute aortic syndrome as Rob has already mentioned and as the authors describe in their introduction of the paper, acute aortic syndrome is an infrequently occurring presentation, but is missed a lot. And we talked about this in our acute aortic syndrome episode. It’s estimated to be misdiagnosed in about a third of cases, and the delay in the cases that are diagnosed up to 24 hours in 25% of them. So, it’s really rare, it’s difficult to spot and then it can often be delayed. And obviously with a presentation that is life threatening, we want to be picking up all the ones that we can, diagnosing them really quickly and then at least being able to intervene as rapidly as possible.”

“So such a challenging area and we’ve picked this paper because it helps really shed light. on the problem and looks to try and find some ways to be able to pick them up more effectively. So, the lead author is McLatchy. It was published just recently in the emergency medicine journal and the title of the paper is Diagnosis of Acute Aortic Syndrome in the Emergency Department the DAShEd study an observational cohort study of people attending the emergency department with symptoms consistent with acute aortic syndrome. I’m sure you’ll have heard about this on social media. It got a lot of appropriately positive attention and commentary to it. So what they’re trying to do in this study is essentially describe the characteristics of patients presenting to ED. With possible acute aortic syndrome and to assess other existing clinical decision tools and use of a CTA in an all-comer cohort of patients. So this isn’t just looking at the problem that in patients who presented with a diagnosed acute aortic syndrome. This is spreading the net really widely and trying to say, of all the patients that come in with possible acute aortic syndrome, how do we then pick out the ones that have actually got it? And that’s the challenge that we all face every day in trying to pick them out.”

Widening the Net

“So they did this in a multi-center observational cohort study of patients who are all 16 years or older attending 27 UK emergency departments and this was at the back end of last year so 2022. For those patients, as we said with potential acute aortic symptoms that started in the last seven days and they define these as things like chest or back pain or abdominal pain, syncope or symptoms relating to malperfusion. So what you’ll be thinking listening to those is that they could be a phenomenal number of different diagnoses and that is obviously the challenge.”

“Now patients were ideally identified with those presentations prospectively but they could also enroll patients retrospectively. Each of these eds had a period of time that they were enrolling these eligible patients, and that was either from two up to 40 days in order to get the information they needed, they collected anonymized data, which included a whole host of information and also the information that’s present in those clinical decision tools that they were gonna go on to evaluate.”

“When the clinicians identified the patients in real-time, so prospectively, they then got those clinicians to essentially quantify. whether or not they thought that acute aortic syndrome was a possible diagnosis and tried to get a feel for how likely those clinicians thought that it might be. So a yes or no answer to could it be acute aortic syndrome and then quantifying it on a likelihood scale from 0 to 10 with an additional question of whether or not they thought it was the most likely diagnosis which is a yes or no answer.

Clinical Patterns and Confirmations

“If the clinician didn’t pop all of that data onto the form, then it could be collected by the local study team. Clinical data included things like time of onset, features of the pain, their medical history and family history, and examination findings. And they used a reference standard of radiological or operative confirmation of acute aortic syndrome in this study.”

“And they also used a 30-day electronic patient record follow-up to see whether or not a subsequent diagnosis of acute aortic syndrome had been made, along with mortality. So, you do need to go and look at the paper here. Because there are loads of things that they’re looking at and why not do that with such a rich data set.

But I’ll run through several of them as we cover the results from the paper. But what they were looking at for definite were the characteristics of their presentation and those decision tools that we’ve mentioned. And also looking to see how CTAs came back as positive.”

The Stark Realities of Diagnosis

“They worked out that they needed 5,000 eligible patients to attend of whom 125 would undergo that CTA and six would have confirmed acute aortic syndrome, they thought, from that group. And they got more than that. They got 5, 500 patients that presented, the median age of 55. What they found was that 14 out of that group had confirmed acute aortic syndrome, which is 0.3%. So now we start to get a real flavour of how difficult it is to pick these patients out. 10 of just over a thousand patients, whom the ED clinician thought that they did have acute aortic syndrome, had it. So 1%.”

“5 out of 147 in whom they thought acute aortic syndrome was considered to be the most likely diagnosis had it. So that means if you’re standing in front of a patient you go, I think this patient’s got acute aortic syndrome. In this study just over 3% of them had it. Two out of over 3,000 patients in whom acute aortic syndrome was considered not possible went on to have it, which is even more scary. And 540 patients from this cohort, so around 10% of them, went on to have a CT. In that 10% of patients who were getting a CT, 2% of them, so 1 in 50, ended up being positive for an acute aortic syndrome. But really interestingly, 40% of all of the CT scans actually detected an alternative diagnosis. And the most common hits that they got here were things like PE, pneumonia, or a non-ruptured aneurysm, acute coronary syndrome, and cholecystitis.”

“They didn’t have any missed acute aortic syndrome diagnoses. And when they looked at decision tools and things like D-dimer, they used a load of different ways to assess their performance, including positive predictive and negative predictive values, sensitivities and specificities. And what they really found is that considering how important it was to make these diagnoses that none of them had precise enough confidence intervals to give them a performance that would be reassuring enough to employ them in clinical practice.”

“So the author’s conclusions here, only 0.3% of patients presenting with potential acute aortic syndrome symptoms had an acute aortic syndrome but 7% underwent CTA. Clinical decision tools incorporating clinician gestalt appear to be most promising, but further prospective work is needed, including evaluation of the role of the D-dimer. So, Rob, that is a massive amount of information, but what were your thoughts on this paper?”

The Urgency in Identification

Rob Fenwick, EM Consultant Nurse, Wrexham Maelor Hospital

“Yes Simon, I mean at the start you said it is a needle in a haystack, but it is in all fairness a very important needle that we would never want to miss and that is because, you know, these acute aortic syndromes are about as serious as it gets, isn’t it? So we’re talking about here, aortic dissections, intramural hematomas and penetrating aortic ulcers and as you’ve said, misdiagnosing a third of patients, over 25% have a delay in diagnosis more than 24 hours and there is a linear increase in mortality by about 0.5% in the first four weeks 48 hours.”

“So it’s tricky, and you know, we’ve previously spoken about the opportunities that are available to us and the challenges on our roadside to resource episode about just this topic. So if you need a refresher, go back there. But from the perspective of this paper, I think it is great to see such a pragmatic and useful set of inclusion criteria being used to get patients into this study. That’s the first thing that jumped out at me.”

Balancing Precision and Practicality

“So as the author state here, we needed to know the incidence of this condition in a truly the undifferentiated population, so not those already deemed to need a CT angio to exclude it, as the thresholds to reach this point will be different between clinicians and different services and different areas of the world, so it’s really important that we understand the incidents which this paper has provided us with, I think.”

“But this paper is tricky to interpret and know what to do with, so I mean the first thing again to say is that 90% of these patients included here didn’t actually get a CTA. So we don’t know definitively that they didn’t have one, if that makes sense. So it does require a little bit more thought. So just looking at some aspects of it that jumped out at me.”

“Well, you know, the clinical decision tools here that they looked at had a sensitivity of 36%, 69% and 77%. So these are certainly not the figures that we’re used to seeing for any clinical decision rules in regular clinical practice and it’s maybe perhaps a little bit more reassuring that an ED clinician likelihood of, I think they said in the paper of more than three out of ten or greater, detected all acute aortic syndrome cases. So perhaps a little bit of good news there but my summary would be that acute aortic syndrome remains a really, really tricky problem and that it should definitely stay, you know, in my mind high up on the research agenda for those in emergency medicine because it seems like we have got a window to benefit these patients like no other speciality has.”

“But at the moment, we don’t really have the research out there to support a particular approach, unless that approach is to do a CT angio on everyone and completely sink radiology. But that’s definitely, you know, not a good idea in my mind to do CTAs on everyone. I think off the back of reading this paper and for the time being it will be my usual approach to these patients or to these suspected patients. So, you know, it’s about taking that detailed history. It’s about considering risk factors. It’s about doing a good clinical examination and potentially then a CTA. If that acute aortic syndrome is still on my list of differentials. But, you know, keep an eye out on that literature to inform you, inform me, inform everyone as much as possible. And this paper has definitely helped to contextualize some of that for me. I don’t think it’s given me huge amounts more information, but the context has been added to greatly by reading this.”

Dilemmas in Diagnosis

Simon Laing, EM Consultant, Bristol Royal Infirmary

“Perhaps this is a bad sign of my own reflection of practice, but it can feel weak, can’t it, at times, for asking for scans with these potential presentations really frequently, and then not getting a positive scan back, because you might be that person that just over investigates everyone. But what this shows is that nobody really knows the right strategy to it. So it doesn’t make it weak. It doesn’t make it the right thing to do. It just nobody knows. What I found really interesting in this is not only to acknowledge it’s a needle in a haystack, but that lots of different diagnoses are being picked up.”

“And what I would love to know is whether or not those diagnoses would have been picked up if the scan wasn’t performed, whether or not it led to any patient benefit. Now that’s obviously a hugely complicated piece of work and it’s not that I’m thinking about setting up a private CT scanning service sort of outside my local emergency department because, I mean, it’s got potential hasn’t it?”

“But this is a brilliant piece of work. I’m sure some people will debate the inclusion criteria and whether or not the seniority of the clinicians, whether or not that comes into it, but it’s pragmatic. It informs our practice, doesn’t it? It doesn’t give us the solution to it, but it does help to explain and then Also, if you’re unlucky enough to be involved in a case that’s missed, it does give some useful context to it, doesn’t it? There’s always lessons to be learned, but it does give some useful context, so would highly recommend people go and have a look at the paper. Great bit of work, thanks to the authors, and we look forward hopefully some further work on the topic from them.”

Towards a Better Understanding

The Resus Room podcast concludes with a profound reflection on the complexities and uncertainties inherent in diagnosing acute aortic syndrome. This reflection, shared by Simon Laing, touches upon the dilemma faced by clinicians in balancing the need for thorough investigation against the risk of over-testing. The episode does not just dissect the DASHED study’s findings; it also offers a broader perspective on the critical role of emergency medicine in diagnosing AAS. It underscores the importance of continuous research and the development of more precise diagnostic tools, leaving listeners with a deeper understanding of the challenges and the ongoing journey towards improving patient outcomes in this critical area of medicine.